- Active Series

- Books

- Online

- Journals

- eBooks

Smell and History: A Reader

Summary

Smell and History collects many of the most important recent essays on the history of scent, aromas, perfumes, and ways of smelling. With an introduction by Mark M. Smith—one of the leading social and cultural historians at work today and the preeminent champion in the United States of the emerging field of sensory history—the volume introduces to undergraduate and graduate students as well as to historians of all fields the richness, relevance, and insightfulness of the olfactory to historical study.

Ranging from antiquity to the present, these ten essays, most of them published since 2003, consider how olfaction and scent have shaped the history of medicine, gender, race-making, class formation, religion, urbanization, colonialism, capitalism, and industrialization; how habits and practices of smelling informed ideas about the Enlightenment, modernity, and memory; how smell shaped perceptions of progress and civilization; and how people throughout history have used smell as a way to organize categories and inform worldviews.

Contents

Editor’s Introduction: Smelling the Past | Mark M. Smith

Introduction: Why Smell the Past? | Alain Corbin

1. Scent and Sacrifice in the Early Christian World | Susan Ashbrook Harvey

2. Urban Smells and Roman Noses | Neville Morley

3. Medieval Smellscapes | C. M. Woolgar

4. Smelling the New World | Holly Dugan

5. Gender, Medicine, and Smell in Seventeenth-Century England | Jennifer Evans

6. Smell and Victorian England | Jonathan Reinarz

7. Reodorizing the Modern Age | Robert Jütte

8. Making “Others” Smell | Mark M. Smith

Epilogue: Futures of Scents Past | David Howes

Acknowledgments

Further Reading

Sources and Permissions

Index

Author

Mark M. Smith is Carolina Distinguished Professor of History at the University of South Carolina. His work has been featured in the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, and the New York Review of Books, and he serves as the general editor of Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Sensory History.

Reviews

“An important overview of this burgeoning new field, compiled by one of its most insightful scholars.”

Peter Denney, Griffith University

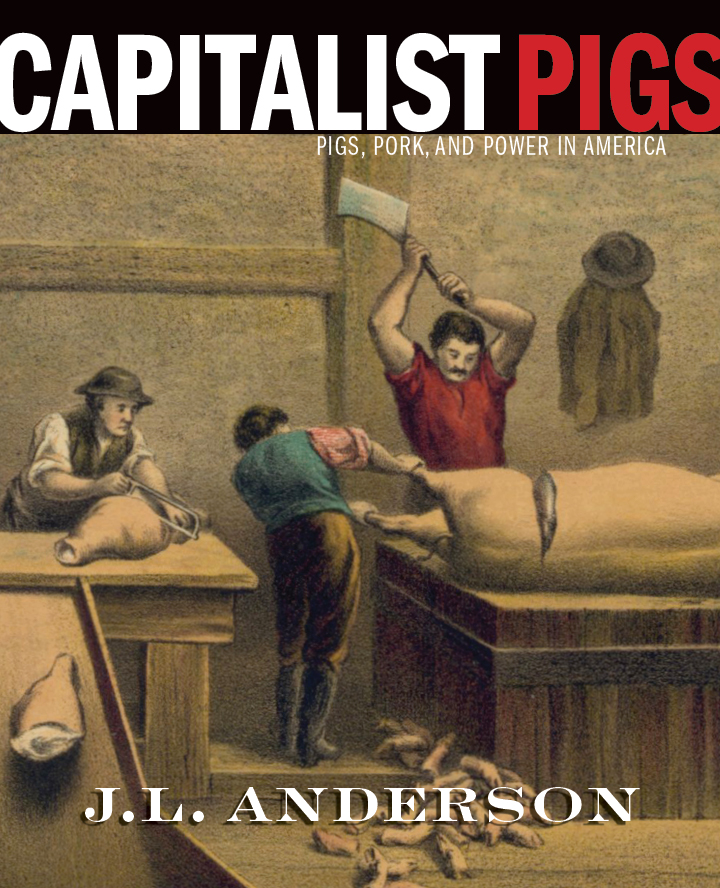

Capitalist Pigs: Pigs, Pork, and Power in America

J. L. Anderson

300pp

PB 978-1-946684-73-8

$34.99

CL 978-1-946684-72-1

Out of print

eBook 978-1-946684-74-5

$34.99

Summary

Pigs are everywhere in United States history. They cleared frontiers and built cities (notably Cincinnati, once known as Porkopolis), served as an early form of welfare, and were at the center of two nineteenth-century “pig wars.” American pork fed the hemisphere; lard literally greased the wheels of capitalism.

J. L. Anderson has written an ambitious history of pigs and pig products from the Columbian exchange to the present, emphasizing critical stories of production, consumption, and waste in American history. He examines different cultural assumptions about pigs to provide a window into the nation’s regional, racial, and class fault lines, and maps where pigs are (and are not) to reveal a deep history of the American landscape. A contribution to American history, food studies, agricultural history, and animal studies, Capitalist Pigs is an accessible, deeply researched, and often surprising portrait of one of the planet’s most consequential interspecies relationships.

Contents

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgments

Introduction

1. Making American Gehography

2. Hogs at Home on the Range

3. Working People’s Food

4. Pigs and the Urban Slop Bucket

5. To Market, to Market

6. Swine Plagues

7. Making Bacon and White Meat

8. Science and the Swineherd

Coda: The Future of Hogs in America

Notes

Index

Author

J. L. Anderson teaches history at Mount Royal University in Calgary, Alberta. Prior to his academic appointment, he was a museum educator and administrator, cultivating a personal and professional interest in swine at the agricultural museums where he worked. Anderson is currently president of the Agricultural History Society.

Reviews

"In the vein of William Cronon’s Nature’s Metropolis, this is a meaty, accessible, and clear-eyed agricultural history."

Booklist

"Anderson delivers the most thorough account of American pigs ever written, a book packed with fascinating detail on where pigs lived (forests, farmyards, city streets), what they ate (nuts, corn, garbage, the corpses of Civil War soldiers), and how scientists transformed their bodies and their lives to meet the relentless demands of the market. This is the story of how pigs made America, and how America remade the pig."

Mark Essig, author of Lesser Beasts: A Snout-to-Tail History of the Humble Pig

“J.L. Anderson weaves a complex story about the hog industry’s impact on the growth of an economy and offers insight into the important role the agriculture and food industry played in the building of a nation. You will find yourself surprised by its influence."

Tom Vilsack, US Secretary of Agriculture, 2009–2017

"J. L. Anderson's Capitalist Pigs is a thorough and engaging examination of swine in US agriculture, culture, and history. It will be a standard to judge later histories of Americans' relationships with agricultural livestock and domestic animals."

Leo Landis, State Curator, State Historical Society of Iowa and "the Bacon Professor"

“A sweeping history of pigs in the United States from before the arrival of Europeans to today. In Anderson’s clear, brisk, and clever history, these animals appear as wild beasts roaming forests, domesticates in farm pens, commodities in railcars, corpses on slaughterhouse hooks, meat at the ends of butchers’ knives, consumer products in Walmart coolers, nourishment in human stomachs, and as transplanted hearts thumping away in human chests. It’s fun to read.”

James C. Giesen, author of Boll Weevil Blues: Cotton, Myth, and Power in the American South

"Anderson’s investigation is thorough, focusing on economic and social impacts, and, when appropriate, unflinching."

Publishers Weekly

"A clear and accessible read, beautifully illustrated with paintings, maps, and photographs that demonstrate the prominence of the pig in America."

Environmental History

"Valuable for scholars and accessible to a broad audience."

The Annuals of Iowa

To the Bones

Summary

2020 Killer Nashville Silver Falchion Award Finalist

Darrick MacBrehon, a government auditor, wakes among the dead. Bloodied and disoriented from a gaping head wound, the man who staggers out of the mine crack in Redbird, West Virginia, is much more powerful—and dangerous—than the one thrown in. An orphan with an unknown past, he must now figure out how to have a future.

Hard-as-nails Lourana Taylor works as a sweepstakes operator and spends her time searching for any clues that might lead to Dreama, her missing daughter. Could this stranger’s tale of a pit of bones be connected? With help from disgraced deputy Marco DeLucca and Zadie Person, a local journalist investigating an acid mine spill, Darrick and Lourana push against everyone who tries to block the truth. Along the way, the bonds of love and friendship are tested, and bodies pile up on both sides.

In a town where the river flows orange and the founding—and controlling—family is rumored to “strip a man to the bones,” the conspiracy that bleeds Redbird runs as deep as the coal veins that feed it.

Author

Valerie Nieman is a professor of English at North Carolina A&T State University. A former journalist and farmer in West Virginia, she is the author of three novels, as well as collections of poetry and short fiction. She is a graduate of West Virginia University, and she received an MFA from Queens University of Charlotte.

Reviews

“This is the West Virginia novel done right: slam-bang storytelling in tightly controlled language, by turns horrific and funny and beautiful.”

Pinckney Benedict, author of Miracle Boy and Other Stories

“In this unusual tale of death and monsters and environmental devastation, horror, science fiction, romance, and satire bleed together to form a vibrant literary delight that is as powerful and imposing as the fearsome orange-hued river that runs through it.”

Colorado Review

“Evocative, intelligent prose conjures an anxious mood and strong sense of place while spotlighting the societal and environmental devastation wrought by the coal mining industry.”

Kirkus Reviews

“A storytelling feat: a pulse-pounding thriller that also manages to construct a whole terrifying, gorgeous mythology. To the Bones surprises and captivates at every turn.”

Clare Beams, author of We Show What We Have Learned

“An immensely readable story of good versus evil, with enough twists and turns (and twists within turns) to keep you guessing to the last minute.”

Steve Weddle, author of Country Hardball

“A thrilling hike into coal country, Nieman’s page-turner pulls off an audacious trick: empathy for a misunderstood region.”

James Tate Hill, author of Academy Gothic

“A creative mix of several genres, including elements of horror, the supernatural, Old Western showdowns, contemporary Southern (complete with a mass outdoor prayer vigil to prepare people for the rapture), suspense and romance.”

News & Record

“An entertaining supernatural thriller about all-too-real threats.”

The Observer

“Nieman has a vivid imagination.”

Salisbury Post

“A heart-pounding, cinematic, and multi-layered story.”

Appalachian Review

Appalachia North: A Memoir

Summary

2019 WCoNA Book of the Year

Appalachia North is the first book-length treatment of the cultural position of northern Appalachia—roughly the portion of the official Appalachian Regional Commission zone that lies above the Mason-Dixon line. For Matthew Ferrence this region fits into a tight space of not-quite: not quite “regular” America and yet not quite Appalachia.

Ferrence’s sense of geographic ambiguity is compounded when he learns that his birthplace in western Pennsylvania is technically not a mountain but, instead, a dissected plateau shaped by the slow, deep cuts of erosion. That discovery is followed by the diagnosis of a brain tumor, setting Ferrence on a journey that is part memoir, part exploration of geology and place. Appalachia North is an investigation of how the labels of Appalachia have been drawn and written, and also a reckoning with how a body always in recovery can, like a region viewed always as a site of extraction, find new territories of growth.

Contents

A Preface (of Sorts)

Acknowledgments

1. Floods

2. This Is Not a Mountain

3. Marginal Appalachia

4. Appalachian Flesh, Appalachian Bone

5. Learning to Say Appalachia

6. The Molt

7. Conduits

8. Reading Like an Appalachian

9. Journey to Canappalachia

10. Coordinates

Bibliography

Author

Matthew Ferrence teaches creative writing at Allegheny College, where he lives and writes at the confluence of the Rust Belt and Appalachia. He and his family divide their time between northwestern Pennsylvania and Prince Edward Island, Canada.

Reviews

"Appalachia North is a lyrical homage to a region often misunderstood and overlooked. Ferrence’s engulfing prose brings to life an Appalachia north of the Mason-Dixon line and he does it with the eye of an honest poet."

Associated Press

“Matthew Ferrence pushes boundaries—literal and figurative—asking difficult questions of himself and of us all. He offers us new metaphors, new maps, new ways to understand ourselves and this world. Hold it, dear reader, and read.”

Jim Minick, author of Fire Is Your Water

“Too often, Appalachian identity gets treated like it’s (a) Southern and (b) the same for everyone. Matthew Ferrence’s insightful, thoughtful essays show us a more refreshing complexity than either of these stereotypes allows. This is a must-read for anyone looking for deeper meaning about Appalachia and life within it.”

Amanda Hayes, author of The Politics of Appalachian Rhetoric

“Beautifully written.”

Pennsylvania History

Far Flung: Improvisations on National Parks, Driving to Russia, Not Marrying a Ranger, the Language of Heartbreak, and Other Natural Disasters

Summary

Cassandra Kircher was in her twenties when she was hired by the National Park Service, landing a life that allowed her to reinvent herself. For four years she collected entrance fees and worked in the dispatch office before being assigned as the first woman to patrol an isolated backcountry district of Colorado’s Rocky Mountain National Park. There, Kircher encountered wonder and beauty, accidents and death. Although she always suspected the mountains might captivate her, she didn’t realize that her adopted landscape would give her strength to confront where she was from—both the Midwest that Willa Cather fans will recognize, and a childhood filled with problems and secrets.

Divided and defined by geographic and psychological space, Far Flung begins in the Rockies but broadens its focus as Kircher negotiates places as distant as Alaska’s Kenai Peninsula, Russia’s Siberian valleys, and Wisconsin’s lake country, always with Colorado as a heartfelt pivot. These thirteen essays depict a woman coming to terms with her adoration for the wilds of the West and will resonate with all of us longing to better understand ourselves and our relationships to the places and people we love most.

Contents

I. Near

A Portrait of My Father in Three Places

Someone Else Dies

There’s an Old Dump Below Lawn Lake

Backcountry Trash (and Other Important Considerations)

Over Mummy Pass

When I Leave

Going to Die

II. Far

On Not Marrying a Ranger

No More to the Lake

Driving to Russia

My Father and I Take a Vacation

Oxford Through the Looking Glass

Visiting the Iditarod Champ

Author

Cassandra Kircher is a professor of English at Elon University. She studied nonfiction at the University of Iowa, and her essays have received awards including a Pushcart nomination and Best American Essays citation. She was the first woman stationed in Rocky Mountain National Park’s remote North Fork subdistrict.

Reviews

“This bold, jaunty narrative travels to unexpected places and tangos with unanticipated obsessions. I can easily imagine Kircher’s book shelved alongside contemporary place-based work by Ana Maria Spagna, Blair Braverman, and Cheryl Strayed.”

Elena Passarello, author of Animals Strike Curious Poses

"Intimate and moving essays on nature, family, and adventures in the wild."

Foreword Reviews

"In a voice as clear and compelling as a tumbling mountain stream, Cassandra Kircher writes of family, landscape, and the deep and sometimes mystical ways in which we are bound to the land and bound to each other. This book is an intimate, meditative journey into the human heart, with no shortage of adventures along the way."

Kristen Iversen, author of Full Body Burden: Growing up in the Nuclear Shadow of Rocky Flats

Lowest White Boy

Greg Bottoms

May 2019

168pp

PB 978-1-946684-96-7

$19.99

eBook 978-1-946684-97-4

$19.99

In Place Series

Summary

An innovative, hybrid work of literary nonfiction, Lowest White Boy takes its title from Lyndon Johnson’s observation during the civil rights era: “If you can convince the lowest white man he’s better than the best colored man, he won’t notice you’re picking his pocket.”

Greg Bottoms writes about growing up white and working class in Tidewater, Virginia, during school desegregation in the 1970s. He offers brief stories that accumulate to reveal the everyday experience of living inside complex, systematic racism that is often invisible to economically and politically disenfranchised white southerners—people who have benefitted from racism in material ways while being damaged by it, he suggests, psychologically and spiritually. Placing personal memories against a backdrop of documentary photography, social history, and cultural critique, Lowest White Boy explores normalized racial animus and reactionary white identity politics, particularly as these are collected and processed in the mind of a child.

Contents

Coming soon.

Author

Greg Bottoms is a professor of English at the University of Vermont. He is the author of many books, including Angelhead: My Brother’s Descent into Madness, The Colorful Apocalypse: Journeys in Outsider Art, and Spiritual American Trash: Portraits from the Margins of Art and Faith.

Reviews

"Greg Bottoms is one of the most innovative and intriguing nonfiction writers at work, and this is his most powerful book to date, a crucial interrogation of whiteness, white supremacy, and the formation of one American lowest white boy."

Jeff Sharlet, author of The Family: The Secret Fundamentalism at the Heart of American Power

“Greg Bottoms takes readers on a journey through ignorance and enlightenment in this dazzling memoir about growing up white and working class in the slowly desegregating South. He treats his subjects with compassion as he explores the tangle of race relations in his childhood. Lowest White Boy should be read alongside Citizen: An American Lyric by Claudia Rankine, in that everyday experiences of racism are illuminated with rich and powerful meaning. A consummate storyteller, Bottoms brings to life a world that is rarely explored in contemporary conversations about racial strife. The result is a narrative that is as beautiful as it is instructive.”

Emily Bernard, author of Black Is the Body: Stories from My Grandmother’s Time, My Mother’s Time, and Mine

“I read Lowest White Boy with serious admiration. It's difficult to think of a timelier, nervier, more discomfiting, more pulse-quickening book than Greg Bottoms’s impressive exploration of an extremely difficult subject. There is candor and then there is candor. This is candor.”

David Shields, author of Black Planet: Facing Race during an NBA Season

“From the first page on, I was totally absorbed in this ‘memoir as vehicle for interpretation,’ as Greg Bottoms describes Lowest White Boy. It’s a passionate hybrid text that moves seamlessly between the personal and the public, the timely and the timeless. Raised in Tidewater, Virginia, ‘at ground zero of American slavery,’ Bottoms imagined as a young boy feeling the ‘layers of time beneath [his] feet.’ A gifted storyteller, he evokes this feeling in each of the poignant, troubling vignettes he offers his lucky readers.”

Rebecca McClanahan, author of The Tribal Knot: A Memoir of Family, Community, and a Century of Change

"A valuable complement to (though not substitute for) the narratives of African Americans, Lowest White Boyshould make readers recall the times when they let the 'stories of their community' override their sense of truth and justice."

Seven Days

LGBTQ Fiction and Poetry from Appalachia

Edited by Jeff Mann and Julia Watts

288pp

PB 978-1-946684-92-9

$29.99

eBook 978-1-946684-93-6

$29.99

Summary

This collection, the first of its kind, gathers original and previously published fiction and poetry from lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer authors from Appalachia. Like much Appalachian literature, these works are pervaded with an attachment to family and the mountain landscape, yet balancing queer and Appalachian identities is an undertaking fraught with conflict. This collection confronts the problematic and complex intersections of place, family, sexuality, gender, and religion with which LGBTQ Appalachians often grapple.

With works by established writers such as Dorothy Allison, Silas House, Ann Pancake, Fenton Johnson, and Nickole Brown and emerging writers such as Savannah Sipple, Rahul Mehta, Mesha Maren, and Jonathan Corcoran, this collection celebrates a literary canon made up of writers who give voice to what it means to be Appalachian and LGBTQ.

Contents

Introduction

Editor’s Notes

Dorothy Allison

Roberts Gas & Dairy

Careful

Butter

Domestic Life

Lisa Alther

Swan Song

Maggie Anderson

Anything You Want, You Got It

Biography

Cleaning the Guns

In Real Life

My Father and Ezra Pound

Nickole Brown

My Book, in Birds

To My Grandmother’s Ghost,

An Invitation for My Grandmother

Ten Questions You’re Afraid to Ask, Answered

Jonathan Corcoran

The Rope Swing

doris diosa davenport

verb my noun: a poem cycle

After the Villagers Go Home: An Allegory

Halloween 2011

Halloween 2017

for Cheryl D my first lover, 41 years later

Three days after the 2017 Solar Eclipse

Sept. 1 Invocation

a conversation with an old friend

Upon realizing

"The Black Atlantic"

Victor Depta

The Desmodontidae

Silas House

How To Be Beautiful

Fenton Johnson

Bad Habits

Charles Lloyd

Wonders

Jeff Mann

Not for Long

Training the Enemy

Yellow-eye Beans

The Gay Redneck Devours Draper Mercantile

Three Crosses

Homecoming

Mesha Maren

Among

Kelly McQuain

Scrape the Velvet from Your Antlers

Brave

Vampirella

Monkey Orchid

Alien Boy

Mercy

Ritual

Rahul Mehta

A Better Life

Ann Pancake

Ricochet

Carter Sickels

Saving

Savannah Sipple

WWJD / about love

WWJD / about letting go

Jesus and I Went to the Wal-Mart

Catfisting

Pork Belly

A List of Times I Thought I Was Gay

Jesus Signs Me Up For a Dating App

Anita Skeen

Double Valentine

How Bodies Fit

Need

Something You Should Know

The Clover Tree

The Quilt: 25 April 1993

While You Sleep

Aaron Smith

Blanket

There’s still one story

Twice

Julia Watts

Handling Dynamite

Selected Bibliography of Same-Sex Desire in Appalachian Literature

Editors

Jeff Mann is an associate professor of English at Virginia Tech. He has published three poetry chapbooks, five full-length books of poetry, two collections of personal essays, a volume of memoir and poetry, three novellas, six novels, and three collections of short fiction. He is the winner of two Lambda Literary Awards.

Julia Watts is a professor of English at South College and a faculty mentor in Murray State University’s low-residency MFA in writing program. She is the author of over a dozen novels, including the Lambda Literary Award-winning Finding H.F., the Lambda Literary and Golden Crown Literary Society Award finalist The Kind of Girl I Am, and the Lambda Literary Award finalist and Golden Crown Literary Award-winning Secret City.

Reviews

“A gratifying diversity of multigenerational voices, styles, and attitudes. The theme of loyalty to place paired with queer identity results in marvelous poetry and fiction.”

Felice Picano, author of Justify My Sins

"An immersive exploration of queer life within the confines of a conservative American subculture."

Foreword Reviews

"The lists of accolades, publications, and prestigious positions attributed to these authors are staggering; the people highlighted in these pages are all well-established and often highly awarded, which implies a much broader collection of queer writers from Appalachia than previously imagined. Many of the authors included here are professors in universities dotted along the outskirts of small Appalachian towns, who must inspire legions of nascent queer writers just beginning to experiment with both writing and their own sexuality."

Lambda Literary

“This collection, through its poetry and prose, maps the queer ecology of Appalachia and the voices that construct themselves in relation to the landscape and the cultural imagination of the place. Each piece in the book unfolds as paradox of both belonging (being from and of a place) and nearly complete alienation.”

Stacey Waite, author of Teaching Queer

“It was a complete pleasure reading this rich collection that explores the gay experience in Appalachia. The urge to flee is strong, but so is the need to return to an at-times brutal terrain that often offers more fists than love.”

Marie Manilla, author of The Patron Saint of Ugly, Shrapnel, and Still Life with Plums

Appalachian Reckoning: A Region Responds to Hillbilly Elegy

Edited by Anthony Harkins and Meredith McCarroll

432pp

PB 978-1-946684-79-0

$28.99

eBook 978-1-946684-80-6

$28.99

Appalachian Reckoning

A Region Responds to Hillbilly Elegy

Summary

2020 American Book Award Winner: Walter & Lillian Lowenfels Criticism Award

2019 Weatherford Award Winner, Nonfiction

With hundreds of thousands of copies sold, a Ron Howard movie in the works, and the rise of its author as a media personality, J. D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis has defined Appalachia for much of the nation. What about Hillbilly Elegy accounts for this explosion of interest during this period of political turmoil? Why have its ideas raised so much controversy? And how can debates about the book catalyze new, more inclusive political agendas for the region’s future?

Appalachian Reckoning is a retort, at turns rigorous, critical, angry, and hopeful, to the long shadow Hillbilly Elegy has cast over the region and its imagining. But it also moves beyond Hillbilly Elegy to allow Appalachians from varied backgrounds to tell their own diverse and complex stories through an imaginative blend of scholarship, prose, poetry, and photography. The essays and creative work collected in Appalachian Reckoning provide a deeply personal portrait of a place that is at once culturally rich and economically distressed, unique and typically American. Complicating simplistic visions that associate the region almost exclusively with death and decay, Appalachian Reckoning makes clear Appalachia’s intellectual vitality, spiritual richness, and progressive possibilities.

Contents

Acknowledgments

Part I. Considering Hillbilly Elegy

Interrogating

Hillbilly Elitism

T. R. C. Hutton;

Social Capital

Jeff Mannp

Once Upon a Time in “Trumpalachia”: Hillbilly Elegy, Personal Choice, and the Blame Game

Dwight B. Billings

Stereotypes on the Syllabus: Exploring Hillbilly Elegy’s Use as an Instructional Text at Colleges and Universities

Elizabeth Catte

Benham, Kentucky, Coalminer / Wise County, Virginia, Landscape

Theresa Burriss

Panning for Gold: A Reflection of Life from Appalachia

Ricardo Nazario y Colón

Will the Real Hillbilly Please Stand Up? Urban Appalachian Migration and Culture Seen through the Lens of Hillbilly Elegy

Roger Guy

What Hillbilly Elegy Reveals about Race in Twenty-First-Century America

Lisa R. Pruitt

Prisons Are Not Innovation

Lou Murrey

Down and Out in Middletown and Jackson: Drugs, Dependency, and Decline in J. D. Vance’s Capitalist Realism

Travis Linnemann and Corina Medley

Responding

Keep Your “Elegy”: The Appalachia I Know Is Very Much Alive

Ivy Brashear

HE Said/SHE Said

Crystal Good

The Hillbilly Miracle and the Fall

Michael E. Maloney

Elegies

Dana Wildsmith

In Defense of J. D. Vance

Kelli Hansel Haywood

It’s Crazy Around Here, I Don’t Know What to Do about It, and I’m Just a Kid

Allen Johnson

“Falling in Love,” Balsam Bald, the Blue Ridge Parkway, 1982

Danielle Dulken

Black Hillbillies Have No Time for Elegies

William H. Turner

Part II. Beyond Hillbilly Elegy

Nothing Familiar

Jesse Graves

History

Jesse Graves

Tether and Plow

Jesse Graves

On and On: Appalachian Accent and Academic Power

Meredith McCarroll

Olivia’s Ninth Birthday Party

Rebecca Kiger

Kentucky, Coming and Going

Kirstin L. Squint

Resistance, or Our Most Worthy Habits

Richard Hague

Notes on a Mountain Man

Jeremy B. Jones

These Stories Sustain Me: The Wyrd-ness of My Appalachia

Edward Karshner

Watch Children

Luke Travis

The Mower—1933

Robert Morgan

Consolidate and Salvage

Chelsea Jack

How Appalachian I Am

Robert Gipe

Aunt Rita along the King Coal Highway, Mingo County, West Virginia

Roger May

Holler

Keith S. Wilson

Loving to Fool with Things

Rachel Wise

Antebellum Cookbook

Kelly Norman Ellis

How to Make Cornbread, or Thoughts on Being an Appalachian from Pennsylvania Who Calls Virginia Home but Now Lives in Georgia

Jim Minick

Tonglen for My Mother

Linda Parsons

Olivia at the Intersection

Meg Wilson

Appalachian Apophenia, or The Psychogeography of Home

Jodie Childers

Canary Dirge

Dale Marie Prenatt

Poet, Priest, and “Poor White Trash”

Elizabeth Hadaway

List of Contributors

Sources and Permissions

Index

Editors

Anthony Harkins is a professor of history at Western Kentucky University in Bowling Green, Kentucky, where he teaches courses in popular culture and twentieth-century United States history and American studies. He is the author of Hillbilly: A Cultural History of an American Icon.

Meredith McCarroll is the director of writing and rhetoric at Bowdoin College, where she teaches courses in writing, American literature, and film. She is the author of Unwhite: Appalachia, Race, and Film.

Reviews

“The most sustained pushback to Vance’s book . . . thus far. It’s a volley of intellectual buckshot from high up alongside the hollow.”

New York Times

“In this illuminating and wide-ranging collection, the authors do more than just debunk the simplistic portrayal of white poverty found in Hillbilly Elegy. They profoundly engage with the class, racial, and political reasons behind a Silicon Valley millionaire’s sudden triumph as the most popular spokesman for what one contributor cleverly calls ‘Trumpalachia.’ This book is a powerful corrective to the imperfect stories told of the white working class, rural life, mountain folk, and the elusive American Dream.”

Nancy Isenberg, author of White Trash: The 400-Year Untold History of Class in America

“So often the song of this place has been reduced to a single off-key voice out of tune and out of touch.Appalachian Reckoningis the sound of the choir, pitch perfect in its capturing of these mountains and theirpeople. This book is not only beautiful, but needed.”

David Joy, author of The Line That Held Us

“A welcome and valuable resource for anyone studying or writing about this much-maligned region.”

Kirkus (starred review)

“Stunning in its intellectual and creative riches.”

Foreword Reviews (starred review)

"While Vance offers one bleak 'window' into the extensive multistate region, this valuable collection shows resilience, hope, and belonging are in Appalachia, too.”

Publishers Weekly

"A book of over 40 essays and poems that bring the real Appalachia to life."

The Bitter Southerner

“A vibrant collection of essays . . . many by women, people of colour and queer people, largely written out of Hillbilly Elegy.”

Times Literary Supplement

“This edited volume continues the rich Appalachian studies tradition of pushing back against one-sided caricatures of Appalachian people. The essays, poems, and photo-essays in this book demonstrate the diversity of Appalachian perspectives on the serious problems facing our nation as well as the role that myths about Appalachia continue to play in US policy debates. This is a must-read for everyone who read (or refused to read) J. D. Vance’s deeply flawed, best-selling memoir, Hillbilly Elegy.”

Shaunna Scott, University of Kentucky

Introduction

Why This Book?

Anthony Harkins and Meredith McCarroll

This is a book born out of frustration. This is a book born out of hope. It attempts to speak for no one and to give voice to many. This is a book that could have emerged without Hillbilly Elegy, but it was also created in the explicit context of a postelection, post–Hillbilly Elegy moment. It therefore attempts to respond to those who have felt they understand Appalachia “now that they have read Hillbilly Elegy” and to push back against and complicate those understandings. It is meant to open a conversation about why that book struck such a deep nerve with many in the region, but it is not meant to demonize J. D. Vance. Instead, the contributors to this book prioritize focusing on the region, reclaiming some of the talk about Appalachia, and offering ideas through the voices of many who have deep, if varied, lived experiences in and of Appalachia.

Either explicitly or implicitly, begrudgingly acknowledged, directly repudiated, or partially welcomed, the shadow of Hillbilly Elegy hangs over this book. Not since Harry Caudill’s Night Comes to the Cumberlands (1963) has a nonfiction book on Appalachia attracted such widespread national acclaim and success as J. D. Vance’s 2016 account, controversially subtitled A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis. As of February 2018, the book had been on the New York Times best-seller list for a remarkable seventy-three weeks in a row and has sold in all formats combined well over a million copies. It ranked first in the combined E-book and nonfiction list for six weeks in 2017 and was the top selling nonfiction ibook of the year.1 It has also received broad critical attention, and has been reviewed across a wide swath of the national media landscape from the National Review and the Wall Street Journal to All Things Considered, Fresh Air, and Slate. In book reviews and on-air interview programs, it has been routinely described as “riveting” and “starkly honest.” “The most important book about America” pronounced the Economist. David Brooks called it “essential reading.” Although such rave reviews have since somewhat abated, Vance himself continues in early 2018 to be a common presence on television and radio interview shows and as a guest speaker, and he was even for a time courted as a potential Republican Senate candidate in Ohio.2

Clearly Vance’s account of growing up in Middletown, Ohio, and visiting eastern Kentucky as a member of a multigenerational family scarred by drug abuse and alcoholism has resonated with many readers, including some Appalachians. Yet, just as obviously, Hillbilly Elegy and Vance have been criticized by many within the Appalachian region and beyond as anti-intellectual, overly anecdotal, and attempting to revitalize widely discredited “culture of poverty” explanations for persistent inequities in the region. Regardless of their particular perspective on Vance, though, all the voices in this book stress that Appalachia is a far more diverse and complex place and identity than Hillbilly Elegy and the media’s interpretation of it imply or that the president tweets about. The people and region belie simplistic definitions or characterizations of a monolithic and predeterminative “hillbilly culture,” as Vance labels it. All of its inhabitants and experiences are not simply an extension of Vance’s individual family and life story, nor should the notion of a “memoir of a culture” (as Vance’s subtitle constructs it) go unchallenged. There is not a single “truth” about Appalachia and its people, and the essays, narratives, and artistic expressions in this book, integrated in the best tradition of Appalachian studies, collectively break up this too solid image of the place simply by speaking multiple truths about multiple experiences. In so doing, they challenge the idea that any single book, including this one, can sum up the entirety of Appalachia and what it means to be Appalachian.

This book provides a platform for reactions to and insights about Vance’s book and its reception but also to writings that reach well beyond Hillbilly Elegy to consider the many ways that Appalachians experience their Appalachianness. As citizens and scholars, Appalachians have been fighting against gross simplifications and stereotypes since at least the early nineteenth century, and this work should be considered only the latest effort to challenge such views.3 Some contributors emphasize the need to challenge distorting and debilitating stereotypes; some stress the need to face the region’s problems forthrightly and squarely. Some are quiet and contemplative; others are angry. Yet despite what the majority of our contributors find to be Hillbilly Elegy’s flaws and even damages, they share the sense that the broader public “rediscovery” of the region that Hillbilly Elegy and the conceptual construction of “Trumpalachia” (in the neologism of contributor Dwight Billings) have engendered should also be seen as an opportunity—a chance to reclaim Appalachia and to help those unfamiliar with the region to recognize its complexities and its diversities.

In this spirit, the contributors address from a range of perspectives an array of pressing questions the Hillbilly Elegy phenomenon raises: What about Vance and his book accounts for the explosion of interest in Appalachia and its people in this historical moment of national political turmoil? Why have the ideas in Hillbilly Elegy caused such a firestorm in the region? What can we learn about both actual Appalachia and the way it is perceived from these reactions and debates? What does it mean in the twenty-first century to be Appalachian? Perhaps most significantly, as poet Jeff Mann explicitly asks here in his poem “Social Capital,” what other Appalachian voices have been drowned out in the flood of attention that Vance and his book have garnered? And how can these voices be heard?

To bring some conceptual structure to this wide range of topics, Appalachian Reckoning is organized broadly into two parts. Part I, “Considering Hillbilly Elegy,” features texts directly assessing or commenting on the words and impact of Vance’s influential work. It is further divided into two sections: a collection of primarily scholarly essays (although also shaped by the authors’ mountain backgrounds and experiences) that carefully consider Hillbilly Elegy through various social and political prisms and a section of personal and autobiographical reflections on the book (although also informed by scholarly analysis). Interspersed throughout part I are poems and photographs that provide artistic responses to Vance’s book.

Part II, “Beyond Hillbilly Elegy,” features narratives and images that together provide a snapshot of a place that is at once progressive, haunted, depressed, beautiful, and culturally and spiritually rich. These stories are difficult to categorize because of their range in voice, focus, perspective, and plot. They are at turns heartbreaking, humorous, contemplative, and defiant. In their broad outlines, they are stories that anyone could tell. But they are stories told by Appalachians, grounded in the specific. The sound of a vowel, the feel of a tool, the recipe for corn pone, the name of a school. There is no singular focal point to part II other than the shared idea that there is no consensus about Appalachia.

* * *

Let us further elaborate on each part of the book, starting with some general thoughts on Hillbilly Elegy and the public persona of J. D. Vance. It is important to recognize the often-stated point that Hillbilly Elegy’s surprising and sustained success is largely a product of the presidential campaign and election of Donald Trump. As others have noted, Vance’s sensational book would most likely have found an audience anyway, since Appalachia is “(re)discovered” cyclically. This political earthquake was the latest shock again bringing Appalachia and some of its people and issues to the forefront of media attention and through that attention to the broader public across the country (and indeed the world).4 The Trump campaign and postelection media coverage have framed one version of Appalachia defined almost exclusively through the prism of the white male coal miner, depressed towns, and rampant opioid addiction. This has served as the perfect signifier of white working-class “forgotten Americans.” In turn, it has led to a partial reconceptualization of the region less as an exotic exception to the rest of America (the “strange land and peculiar people” mindset that has so characterized views of the region since at least the nineteenth century) and instead more as an intensified signifier of the hazily defined conceptual category of “the white working class”—regardless of both the concept’s and the region’s actual geographic, demographic, and cultural diversity.5

There is also appeal for many in Vance’s ability to transcend his early childhood traumas and in his simple and personalized account of that transcendence. Vance’s story, largely devoid of analyses of broader socioeconomic and historical dynamics, is compelling—the quintessential “up from your bootstraps” “American Dream,” as he often notes. He describes growing up in an unstable, nontraditional, lower middle-class household and experiencing harrowing moments navigating childhood and early adulthood with a drug-dependent, dysfunctional mother. Overcoming a long string of ineffectual and uncommitted stepfathers and his mom’s boyfriends, and an extended family prone to violence, he is cared for by his strong and loving, if “crazy hillbilly,” maternal grandmother and generally hardworking maternal grandfather. Vance barely avoids becoming a high school dropout, joins the Marines upon graduation to get his life in order, and graduates early and summa cum laude from Ohio State University. A degree from Yale Law School and marriage to a classmate complete his transformation into the upper class. Vance’s story of transformation may not be over, since Hillbilly Elegy’s phenomenal success has launched him into the role of pundit and potential national politician. As some of our contributors stress, this end result is crucial to both the book’s appeal and his claims to hillbilly authenticity. Despite his hardscrabble beginnings, only his later success in the world of law and politics and the valuable personal connections he has made (with the likes of billionaire businessman and investor Peter Thiel and Yale University “tiger mom” Amy Chua) make him seem a legitimate “spokesperson for the white working class.” In other words, only in distancing himself from Appalachia and what he dubs “greater Appalachia” has Vance come to be seen as the “authentic” and “credible” voice of the region and the white working class.

This is not meant to blithely dismiss the obvious appeal of the book for so many as simply a form of “false consciousness.” Nor is it meant to discount the legitimacy of the issues his book and life story bring to the foreground, including the devastating impact of drug abuse and addiction, particularly in rural America and Appalachia; the economic and social debilitation brought on by the collapse of the old industrial economy and the jobs so many relied upon; the sustaining power of intergenerational bonds and the importance of positive role models and social stabilizers; and the deep sense of cynicism, pessimism, and resignation felt by many, especially older white men in non-coastal America. But it is important to also consider what it is about the story he tells that makes it such an appealing vision to many Americans of a variety of political stripes who so desperately want to believe that the “American Dream” (a term that Vance repeatedly uses but never really defines) is still possible—especially because they also fully recognize how the country is characterized by deep economic and political inequities and injustices.

The ideas and contradictions introduced above are explored and elaborated on in part I of the book. The essays in the first section, “Interrogating,” assess the accuracy of Vance’s so-called memoir of a culture and seek to illuminate the ways Hillbilly Elegy and its social impact are tied to powerful political ideologies and institutions active in America today. Historian T. R. C. Hutton begins by critiquing the book as an unrealistic modern-day Horatio Alger tale of advancement over economic and familial obstacles through “luck and pluck” that rejuvenates long-discredited “culture of poverty” arguments to explain the hardships the region faces. He argues this approach erases larger socioeconomic factors, relies falsely on ethnic determinism, and essentializes working-class society. Sociologist Dwight Billings reflects critically on the way the book has been embraced, in the wake of the election of 2016 and the Trump presidency, by neoliberals in both major political parties and contributed to the idea of a mythical realm he dubs “Trumpalachia.” However, Billings argues that the region, rather than being inherently “the reddest of red state America,” is potentially far more politically progressive than the media and both political parties have acknowledged or Vance’s book implies. Next, public historian and writer Elizabeth Catte considers the causes and implications of the book being featured as the selection of a campus or community-wide “one read” book program by many colleges and universities. She concludes that one effect is to too narrowly define who and what Appalachia is and, more problematically, is not. Urban migration scholar Roger Guy then considers the accuracy of the book’s portrayal of the urban Appalachian migrant experience, comparing Vance’s account and experience with those of twentieth-century Appalachian migrants to Chicago and other Midwestern cities. He explores multigenerational patterns of work and life for Appalachian out-migrant and shuttle-migrant communities, concluding that Vance’s story of familial violence and degradation contrasts with the experiences of most first- and second-generation migrants.

The remaining essays under “Interrogating” consider the messages of the book through the prisms of race and racial ideology and drug addiction and criminality. Although she empathizes with Vance’s emotional journey and appreciates his attention to place, class, and culture, legal scholar Lisa Pruitt ultimately sees the book as more of a distortion than an illumination of white socioeconomic disadvantage. She argues that by understating the positive role of the state in his own life trajectory (especially the military and public higher education), erasing the concept of white privilege, and presenting the idea of “hillbilly” as strictly a cultural and not a racial identity and construction, Vance promotes the myth of a society based on true meritocracy so dear to white elites largely ignorant of the reality of systemic working-class inequity. Travis Linnemann and Corina Medley, analysts of media representations of justice, focus instead on the portrayal of the drug abuse and addiction that is so central to Hillbilly Elegy as well as to the ways Appalachia has come to be perceived as ground zero of this nationwide epidemic. While in no way discounting the seriousness of this crisis, these authors argue that by erasing broader social and historical forces and explanations, Hillbilly Elegy offers a form of victim blaming in which drug abuse becomes nearly the sole explanation for familial and social ill fortunes rather than a symptom of larger debilitating forces of neoliberal capitalism.

“Responding,” the second section of part I, offers the individual reactions of five very different Appalachians who see the book as resonating with, or more often diverging from, their own personal and familial experiences. Ivy Brashear, Michael Maloney, Kelli Haywood, Allen Johnson, and William Turner offer eloquent and heartfelt responses to Vance’s portrayal of growing up in Appalachia and southern Ohio. Community activist Brashear forcefully condemns the book for distorting the complexity of the region, erasing the history of “oppressive systems of extraction,” and leaving the impression that all Appalachian families share the same dysfunction as Vance’s own. She reveals this destructive history through sharing her own family’s generations-long experiences of resisting exploitation and supporting one another emotionally. Brashear further challenges Vance’s narrative by telling her own story of a typical American childhood in Perry County, Kentucky, building forts, playing Nintendo, and going to prom. Michael Maloney’s narrative is grounded in his own geographically similar history to that of Vance, having grown up just outside of Jasper, Kentucky (where Vance spent many of his summers with his grandparents), and later in the southern Ohio towns around Cincinnati near Middletown where Vance was raised. Maloney also draws on his decades of work assisting urban migrant communities to explore the ways Appalachian migrants have dealt with the hardships of economic relocation and eventual deindustrialization. Although he acknowledges the problems with Vance’s understating of systemic causes, he also sees much truth and value in Vance’s story and ends with a call to embrace Vance as a means to achieve better public policy in Appalachia and Appalachian migrant communities in the wake of deindustrialization, globalization, and automation.

Kelli Haywood largely defends the book as a powerful and honest personal account of the harsh realities of the lives of many living in the mountains. She argues that though Vance’s portrait is at times simplistic, it nonetheless brings uncomfortable truths to the foreground and highlights a litany of negative statistics—a reality that must be faced squarely if the region as a whole is to advance. Allen Johnson offers yet a different take from his perspective as a rural West Virginian with decades of experience in social services, ministry, environmental stewardship, and raising a family. Although he does not personally share Vance’s rough origin story, Johnson praises the book as a window into and model of the central role of what he calls “transcenders”—individuals who are able to overcome adverse childhood experiences to become successful and fulfilled adults. Finally, sociologist and researcher William Turner offers his unique perspective as both an African American who grew up in the coalfields of southeastern Kentucky and a leading scholar of the history of blacks in Appalachia and out-migration communities. Drawing on his own remarkable achievements and those of so many of his classmates from Lynch (Kentucky) Colored School and others in the self-named “Eastern Kentucky Social Club,” Turner stresses the total absence of African Americans from Vance’s book and from national views of the hardships of the people of the region. These conceptions exist, he argues, despite the fact that blue-collar black migrants collectively both have disproportionately suffered more than blue-collar whites from deindustrialization and have proven more resilient in the face of these difficulties.

Scholarly essays and personal narratives are not the only ways Appalachians have grappled with Hillbilly Elegy and its regional and national reception. Part I therefore also includes a selection of poems and photographs that reveal other ways of envisioning what Vance gets right and wrong about the region. Jeff Mann’s poem “Social Capital” captures the ways Vance simultaneously illuminates and erases this elusive if powerful idea, whereas Ricardo Nazario y Colón’s “Panning for Gold” frames the book as the latest contribution to the “politics of poverty” show. Crystal Good’s “HE Said/SHE Said” rejects Vance as representative of her Appalachian experience; Dana Wildsmith’s “Elegies” sympathetically ties Vance to an earlier Appalachian voice of cultural celebration and lamentation. The photographs and explanatory notes of Theresa Burriss, Lou Murrey, and Danielle Dulken offer yet other ways to consider a region shaped by the dignity of hard work and devastating environmental degradation, diversity and activism, and countless stories of the joys and sorrows of everyday people.

* * *

When the War on Poverty came to Appalachia in the early 1960s, many felt that the region’s story was being told by the wrong voices. Or at least too few voices. After President Johnson traveled to Appalachia in 1964 to bring media attention to its needs as part of his launch of this massive economic support program, many filmmakers and documentary crews followed those well-rutted dirt roads into the same hollows. Charles Kuralt’s Christmas in Appalachia (CBS, 1965) had the broadest reach, but other filmmakers swept in to capture familiar images and tell familiar stories about a complex place.6 One response to this wave of cinematic depictions of Appalachia was the desire to empower residents of those places to tell their own stories and make their own films. The result was Appalshop, a nonprofit cultural arts organization that opened its doors in 1969, funded by the Office of Economic Opportunity along with the American Film Institute. The War on Poverty that paved the path for simplistic representations of Appalachia, therefore, also helped launch an organization dedicated to countering and complicating those narratives and to giving voice to more people living in the region—to allow them to tell their own stories.7

In the same way, the collection of personal narratives that make up part II of this book, “Beyond Hillbilly Elegy,” was imagined partly in response to the noise surrounding Vance’s book and took as its inspiration other recent collections of astute and powerful Appalachian writers.8 A good way to quiet one voice is to add other voices to it. Simply put, that is the aim of this collection of stories and reflections on Appalachia. Casting a wide net, the narratives collected here give voice to a broad range of Appalachian writers who, just by sharing their stories, complicate the narrow story often told about this place. These stories defy the limited Appalachia that Vance sells in his book. They hail from different parts of the region; they boast different racial identities and sexual orientations and represent diverse life stories. Young as well as seasoned, they are educators, activists, poets, photographers, mothers, fathers, brothers, and sisters. And they come from a long Appalachian tradition of speaking up and talking back.9 These personal narratives range in content and context widely but are all grounded in specific Appalachian experiences. Many focus on capturing movement into and out of Appalachia from a new generation’s perspective. Some writers grapple with what it means to be Appalachian as they leave the region and understand how others have framed it for them. When a place is defined for them, they ask, how much power do they have to define it themselves? Other writers and poets ask similar questions but from within the region. Seeing a changing landscape and culture, they work to maintain connections to traditions of their elders, and to pass those along to a new generation. Some strive to escape parts of their inheritances while celebrating others. Part II deals with the way others have seen us (as snake handlers, as mountain men, as Deliverance extras) and the more complex ways that we try to see ourselves. And like people from anywhere, no one marker of identity suffices. But unlike people from some places, all these Appalachians feel a strong need to define themselves in opposition to the (mis)defining that others are doing on our behalf. The contributors are all reclaiming Appalachia in their way.

Part II begins with three poems from Jesse Graves, each an expression of a bodily connection to place—generations deep, yet never stagnant. Meredith McCarroll laments the ways that she shifted her accent as she spent more time in academia, and celebrates the opportunity to reclaim and integrate layers of identity. A photograph from Rebecca Kiger, the first of four featured here from Looking at Appalachia, the crowd-sourced photography project launched by Roger May, challenges negative perceptions of downtrodden Appalachians and shows them instead as strong, vital, and joyous. In “Kentucky, Coming and Going,” Kirstin Squint wrestles with family legacies and lore, asking what it means to be from a place, to leave a place, and to claim a place as your own. Poet Richard Hague defiantly celebrates Appalachia in his poem “Resistance, or Our Most Worthy Habits.” Jeremy B. Jones recalls being called a mountain man and reflects on the multiplicity of being a ninth-generation mountaineer, but he also thinks about Ernest T. Bass and The Andy Griffith Show and the legacy of labels we inherit without claim. Edward Karshner, too, remembers the sting of being characterized as a “hillbilly,” and later comes to revel in the stories that he passes down to his own children—complicated by his rich knowledge of language and its implications in Appalachia and what he calls the “Off.” Luke Travis’s photograph, set in Pittsburgh, reminds him that the small-town values he knew from childhood make their way into the city. In “The Mower—1933,” Robert Morgan crafts a tangible description of work as he both conquers and communes with the land that he knows so well. Chelsea Jack’s story of leaving and finding home is tied to her mother’s labor, her family’s mobility, and her ability to bring with her that which was left behind.

Robert Gipe traces his own path through Appalachia, enabled by his mother’s humor and sense of voice, which allows him to work, through storytelling, with his community in Harlan County. Roger May’s photograph “Aunt Rita along the King Coal Highway, Mingo County, West Virginia” defies elegy and celebrates home. Poet Keith S. Wilson’s series “Holler” explores travel and migration, belonging and not belonging—both inside and outside of Appalachia. Through close readings and reflections empowered both by theory and experiences of class migration, Chelsea Jack writes about the tension of finding one’s place in the out-of-place. Inspired by antebellum texts and imaginings of new freedom, Kelly Norman Ellis contributes two poems that situate the black female body squarely in the mountains of the American South. In the form of a recipe, Jim Minick reflects on homesteading, cornbread, migration, and home. In “Tonglen for My Mother,” Linda Parsons reflects on suffering, compassion, and peace. Meg Wilson’s photograph “Olivia at the Intersection” captures a small moment on a Friday night when community fills the streets in its own Appalachian celebration. Jodie Childers’s vivid recollection of caretaking winds us through her own comings and goings in and out of Appalachia, in and out of her familial role. In “Canary Dirge,” Dale Marie Prenatt directly and bitterly calls on America to see itself in Appalachia. Finally, Elizabeth Hadaway writes about her experiences being stereotyped, both in academia and in the ministry—where she learned, at last, how to handle the snakes that surrounded her.

Collectively, the scholarship, personal reflections, poetry, and photography in this book offer a rejoinder to the national reportage on Appalachia that is rooted in the Hillbilly Elegy phenomenon and that defines the region monochromatically and almost completely in terms of backwardness, ignorance, isolation, violence, dependency, and passivity, ultimately as a place of social, economic, and cultural death. This book instead presents a very different Appalachia and Appalachians—a place and people with undeniable problems but also intellectual vitality, diversity (in terms of ideology, gender and sexuality, race and ethnicity), and a powerful resilience. It is these characteristics that are lost in imagining Hillbilly Elegy as the sole window into the Appalachian experience.

* * *

On the closing day of the 2018 Appalachian Studies Association conference in Cincinnati, J. D. Vance was an invited panelist alongside ethnographer and journalist Wendy Welch on the topic of poverty and the opioid epidemic. The presence of Vance was deeply upsetting and disruptive to many engaged in the work around Appalachia. In response, Y’ALL (Young Appalachian Leaders and Learners) organized a protest of Vance, turning their chairs and bodies to the back of the room when he spoke, periodically booing and talking back to him, and singing “Which Side Are You On?,” a protest song written in 1931 by Florence Reece during the Harlan County Mine Wars. Many supported this demonstration of anger and frustration, but others tried to quiet the protesters. The aftermath of Vance’s presence at ASA has exposed a problematic generational divide within the organization as well as a call by Y’ALL for reforms to the process of organizing and convening panels at the national conference.

Painful as this experience has been for many, we also see it as offering opportunities for greater understanding and dialogue that we hope this book can help fulfill. At a time in which policy making too often takes the form of 140-character tweets, Russian bots decipher our online profiles in order to influence the way that we vote by creating extreme division, and differences among us seem to create insurmountable chasms, we desperately need a space to open up, listen, make room, and disagree with respectful candor. This does not mean treating all sides and all forces as equally valid. When Florence Reece wrote and performed “Which Side Are You On?,” it functioned as a moral rallying cry to wake people in and beyond the region and to align them with the workers around them rather than the company that exploited them. We do not need to smooth out our differences or silence protestors or shout down those with whom we disagree, or shame someone who has a story to tell. Rather, we need to magnify the ways we are unique, give voice to all who want to contribute a verse, and acknowledge the full range of experiences that constitute Appalachia.

Postelection America has made it strange to be from Appalachia. Many of us have not liked the way that Hillbilly Elegy has been used as a shorthand way to explain the Trump phenomenon. While it is frustrating to have one person speak for a place, it is worse to have so many people listen to that one person and assume that he’s right and representative of all of Appalachia. Contributor Elizabeth Catte recently recalled in her blog the way she addressed the question of audience at a talk at West Virginia University, writing, “I think self-definition is power and if I tell you what or who you are I have taken some power from you and I do not want to do that.”10 So when coworkers in Maine or in-laws in Florida or even college friends in western Kentucky say that they now understand Appalachia because they have read Hillbilly Elegy, it strikes a nerve. We’ve been defined by so many journalists and filmmakers over the years who’ve briefly dropped in only to confirm what they already suspected, and we’re sick of it.

So we’re passing the microphone. We’re making room for scholars who have spent careers thinking about poverty and family and race and labor and addiction to share what they know about some of the topics that Vance touches on in Hillbilly Elegy. We are carving out space for more people to tell their family stories, their Appalachian memories, their lived experiences, and their views of future Appalachias. Inspired by Looking at Appalachia, we are featuring powerful and poignant images that resonate with the writings and offer a perhaps unexpected window into what it means to be Appalachian.11 May this collection of scholarship, poetry, photography, and personal narrative remind us all that there is and always has been space to differ, to disagree, to protest, to rage, to reimagine, to commemorate, and to learn. There is space for all of us to reclaim Appalachia as it is for us. And there is a desperate need for the fierce hope embedded in these grounded critiques, humorous anecdotes, and captured moments. Let this book inspire a fierce hope for Appalachia.

Notes

- “Combined Print and E-Book Nonfiction,” New York Times, February 11, 2018, https://nyti.ms/2BjQKkv; Jim Milliot, “Print Units through September Up 2%: Sales of Popular Backlist Books Offset the Lack of New Blockbuster,” Publishers Weekly, October 6, 2017, https://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/bookselling/….

- For a sampling of such reactions, see https://www.harpercollins.com/9780062300546/hillbilly-elegy. On Vance’s Senate decision, see Kevin Robillard, “J. D. Vance Passes on Senate Run in Ohio,” Politico, January 19, 2018, https://www.politico.com/story/2018/01/19/jd-vance-no-senate-run-ohio-3….

- For an overview of some of these important efforts, see Stephen L. Fisher, Fighting Back in Appalachia: Traditions of Resistance and Change (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1993); Dwight Billings, Gurney Norman, and Katherine Ledford, eds., Back Talk from Appalachia: Confronting Stereotypes (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1999); Stephen L. Fisher and Barbara Ellen Smith, eds., Transforming Places: Lessons from Appalachia (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2012); and, most recently, Elizabeth Catte, What You Are Getting Wrong about Appalachia (Cleveland: Belt, 2017).

- The idea that the book would have found an audience is from Joshua Rothman, “The Lives of Poor White People,” New Yorker, September 12, 2016, https://www.newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/the-lives-of-poor-wh…. On the continual “rediscovery” of Appalachia, see Catte, What You Are Getting Wrong, especially pt. II; Allen W. Batteau, The Invention of Appalachia (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1990); Henry D. Shapiro, Appalachia on Our Mind: The Southern Mountains and Mountaineers in the American Consciousness, 1870–1920 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1978); Emily Satterwhite, Dear Appalachia: Readers, Identity, and Popular Fiction since 1878 (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2011); and Billings, Norman, and Ledford, Back Talk from Appalachia.

- The phrase “Strange Land and a Peculiar People” comes from an 1873 article by Will Wallace Harney. On this tradition, see Anthony Harkins, Hillbilly: A Culture History of an American Icon (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003), 29–45.

- See Harkins, Hillbilly, 184–86; Batteau, Invention of Appalachia, chaps. 8–9; Ron Eller, Uneven Ground: Appalachia since 1945 (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2013), 80–82, 102–3; Meredith McCarroll, Unwhite: Appalachia, Race, and Film (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2018), chap. 4.

- Appalshop, https://www.appalshop.org/about-us/our-story/; Stephen P. Hanna, “Appalshop,” in Encyclopedia of Appalachia (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2006), 1693–94, and “Three Decades of Appalshop Films: Representations, Strategies, and Regional Politics,” Appalachian Journal 25, no. 4 (Summer 1998).

- Adrian Blevins and Karen Salyer McElmurray, eds., Walk Till the Dogs Get Mean: Meditations on the Forbidden from Contemporary Appalachia (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2015); Charles Dodd White and Larry Smith, eds., Appalachia Now: Short Stories of Contemporary Appalachia (Huron, OH: Bottom Dog Press, 2015).

- Thanks to Theresa Burriss for helping us appreciate this spectrum and put it into words.

- Elizabeth Catte, “A Message to the Future of Appalachia,” https://elizabethcatte.com/2018/04/16/future/.

- Looking at Appalachia, http://lookingatappalachia.org/.

Beyond The Good Earth: Transnational Perspectives on Pearl S. Buck

Edited by Jay Cole and John R. Haddad

204pp

PB 978-1-946684-75-2

$24.99

eBook 978-1-946684-76-9

$24.99

Summary

How well do we really know Pearl S. Buck? Many think of Buck solely as the Nobel laureate and Pulitzer Prize–winning author of The Good Earth, the novel that explained China to Americans in the 1930s. But Buck was more than a novelist and interpreter of China. As the essays in Beyond The Good Earth show, she possessed other passions and projects, some of which are just now coming into focus.

Who knew, for example, that Buck imagined and helped define multiculturalism long before it became a widely known concept? Or that she founded an adoption agency to locate homes for biracial children from Asia? Indeed, few are aware that she advocated successfully for a genocide convention after World War II and was ahead of her time in envisioning a place for human rights in American foreign policy. Buck’s literary works, often dismissed as simple portrayals of Chinese life, carried a surprising degree of innovation as she experimented with the styles and strategies of modernist artists.

In Beyond The Good Earth, scholars and writers from the United States and China explore these and other often overlooked topics from the life of Pearl S. Buck, positioning her career in the context of recent scholarship on transnational humanitarian activism, women’s rights activism, and civil rights activism.

Contents

Introduction

Jay Cole and John Rogers Haddad

1. Pearl Buck, Raphael Lemkin, and the Struggle for the Genocide Convention

David M. Crowe

2. Pearl Buck and the Evolution of American Foreign Policy: Reflections and Speculations of Her Film Biographer

Donn Rogosin

3. Pearl Buck’s Strategic Vision: Decolonization, Desegregation, and Second World War Imperatives

Charles Kupfer

4. Chinese Culture “Going Global”: Pearl S. Buck’s Methodological Inspiration

Junwei Yao

5. Pearl S. Buck’s Promising Legacy in South Korea: The Pearl S. Buck Foundation and the Rise of Korean Multiculturalism

T.J. Park

6. “Always in Love with Great Ends”: Pearl S. Buck on Sun Yatsen and His Nationalist Revolution

David Gordon

7. China’s Recent Realization: The Real Peasant Life Portrayed by Pearl S. Buck

Kang Liao

8. Gateways into The Good Earth: Myth, Archetype and Symbol in Pearl S. Buck’s Classic Novel

Carol Breslin

9. “Not Having to Be Alone Is Happiness”: The Cal Price Writing Workshops at the Pearl Buck Birthplace as Catalysts for a Glocal Writing Community

Rob Merritt

Contributors

Index

Author

Jay Cole serves as senior advisor to the president of West Virginia University. He teaches courses about Pearl S. Buck as part of the WVU Osher Lifelong Learning Institute, and he is a member of the Pearl S. Buck Birthplace Foundation board of directors.

John R. Haddad chairs the American studies program at Penn State Harrisburg. He is the author of The Romance of China: Excursions to China in U.S. Culture, 1776–1876 and America’s First Adventure in China: Trade, Treaties, Opium, and Salvation.

Reviews

“The strength of this collection lies in the breadth and variety of the subjects discussed, from US foreign policy to literary and political controversies in China to Pearl Buck’s accomplishments and influence as a writer and as a social and political activist. Taken collectively, these essays provide a rewarding survey.”

Peter Conn, author of Pearl S. Buck: A Cultural Biography